In antiquity, anatomical votive offerings were given to the Gods, typically to Asklepios and other deities whose cultus was interwoven with healthcare before the temples were destroyed. When I was diagnosed with something that needed to be surgically removed, though, due to the long tradition of her association with gynecological matters, I decided that I would give an anatomical votive offering to Artemis. This post provides some Platonic sense-making context (AKA “stuff that came up in my head as I was biding my time until surgery”), goes into what happened, and concludes with a few resources linking you to images of votive items.

One of the reasons many people are silent about gynecology is that it seems related to sexual activity, when in fact gynecology is about a lot more than that, and I think it’s worth taking time to get to body-neutral when we talk about organs that about half of the population has, and not just because I am trying to find justification for giving people Hypatia-and-the-rag moments. The lack of frankness about these medical topics contribute to a lack of cultural and political understanding of what is at stake when gynecological services are stigmatized and not readily available. From a theological standpoint, it also contributes to ignorance in how to conceptualize what is happening in the Platonic tradition when authors like Proclus talk about “male and female” being rooted quite high up in the metaphysical hierarchy, as he isn’t talking about social gender and/or human cultural roles, but about mammalian reproductive processes, which can serve as ready starting points when discussing what happens in different “generations” of Gods as the hypostases move “from” the One and the Henads “to” embodied, encosmic multiplicity.

Cat Bohannon’s Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution is a great place to start. This recently-published book looks at mammalian evolution and how it impacts people today. She starts out the book with a gripping story about how liposuction of the parts of the body where special fat deposits are made to ensure that the fetus doesn’t kill the mother (due to our brain size, we need lots of tasty omegas) makes the fat organ freak out and grow new deposits on arms and elsewhere. We didn’t know that this is how the body would react. The fetus, and then the child, wants to take as many resources as possible to survive; the mother wants to ensure that the next generation survives, but that it doesn’t take enough to kill her. Many gynecological problems are echoes of the births of everyone who has come down before us, from the rodent-like ancestors alive during the time of dinosaurs to the more recent hominids.

We could characterize this as (roughly) half of the population having a same-other conflict within their own bodies, regardless of whether or not someone with these organs ever gets pregnant. This was even evident in the ancient world, millennia before we knew what an ovum was in a mammalian sense or that the ovum has some active selection of how it is fertilized or had robust gynecological services to prevent maternal deaths.

This same-other conflict is, in a sense, what Proclus is getting at when he discusses why deities who have more to do with separation and bringing things forth towards generation are often classified with the term “female.”

Very properly therefore, in the second genera of the Gods also, union is derived from the male, but separation from the female divinities. And bound indeed proceeds from the males, but infinity from the females. For the male is analogous to bound, but the female to infinity. The female, however, differs from infinite power, so far as power indeed, is united to the father, and is in him; but the female is divided from the paternal cause. For power is not only in the female divinities, but is also prior to them, since the intelligible powers are in the male divinities, according to Timæus, who says that the power of the demiurgus is the cause of the generation of perpetual natures. For [the demiurgus says to the junior Gods] “imitating my power, produce and generate animals.” Power therefore, is prior to the male and the female, and is in both, and posterior to both. For it pervades through all beings, and every being participates of power, as the Elean guest says. For power is every where. But the female participates in a greater degree of its peculiarity, and the male of union according to bound. That the first number therefore, which presents itself to the view from intelligibles, is of a feminine nature, is through these things evident.

Proclus, Theology of Plato, Book 4, Chapter 30

Just as, at the end of the Parmenides commentary, Proclus points out that our struggle towards the One points out more about ourselves than it does about the One because it is still trapped within our psychology (as the final leap can only be a gift from the Gods), these classifications are a window on how we view Gods from the lens of our own embodiment. A hypothetical civilizational species descended from sea horses, where males get pregnant, or kangaroos, which give birth with envious ease, or even birds, would have a totally different way of attributing sex and gender to Gods whom we view as very clear-cut, from Demeter to Rhea to Artemis to Ares to Hephaestus. (They would still make a division between who has more and less contact with what is posterior, but it would follow signs and tokens and traces that are more evident to them.) While the deities whom we call Goddesses and Mothers, or even Zeus-as-Mother to Athene or Dionysos, have contact with their offspring, they are Gods, and they can pour forth good upon the offspring unceasingly and without diminishing themselves. We, as mortals, cannot give without limit.

This capacity has, for millennia, been used as an important theurgic symbol in our species in its own right, not only when reproductive capacity is tied up with romance. While the discussion of what it means has been used to misogynistic ends on occasion, there is no need for it to be that way, as procession into the embodied cosmos is a good even if individual partial souls like us often have a rough go at it until we find our footing. The capacity to bring forth the next generation is a theurgic symbol that indexes against the Parthenoi, the Goddesses who have reproductive capacity and choose not to make use of it, as well as among those who do, who are mothers, wives, and lovers. Nothing of us would be possible without Mother Rhea, the vivific mediator between Kronos and Zeus.

During my adulthood, and especially since starting to read Platonic texts, I’ve thought about these many passages in the context of my own issues. At 36, I am unlikely to ever have children, and due to my sexual orientation, I have never needed birth control to prevent pregnancy. Despite having no active contact with my own generative capacity in the slightest, I have had menorrhagia for most of my adulthood. It got worse and weirder in 2020, so I’ve suffered more over the past few years. In a profession dominated by women, and having graduated from a women’s college, I’ve also benefitted from being in social contexts where mild discussion of nonsexual reproductive health, such as periods, perimenopause, breast cancer prevention, and so on, are normal. It’s only when I bring up these topics outside of my usual social bubble that I realize that most people either sexualize anything to do with gynecology or think it’s over-the-top body horror. The ways in which I come into contact with that same-other conflict are things like what has happened over the past few months. Needing a surgical procedure made me keenly aware of the otherness of my own reproductive system, despite it being in my lower abdomen.

It started in November, when I scheduled an urgent medical appointment due to some new sharp pain symptoms. I heard phrases like “we have to get this out,” “FWIW there’s a small risk this is cancer but don’t worry,” and “if you have this done in the office, there will be a lot of blood, and you will be screaming.” I’ve never seen that doctor before because the thing about urgent visits is that you sort of go with whichever one in the practice is available ASAP and trust that the electronic record system will sort out the rest. So I signed some things about surgery consent and went home.

The procedure that doctor wanted to do was an outpatient surgery under general anesthesia, and anesthesia has, in the past, made me so nauseous that I couldn’t keep liquids down for a few days. In gynecology, they don’t do stitches or give antibiotics for minor surgeries, so they instead rely on “lift no more than 15 pounds” for the healing time duration to prevent the wound reopening and getting infected. That’s easy to say for someone with a partner or family nearby to help, but I have to haul laundry to the laundromat, clean the cat litter, and take out the trash all on my own. I didn’t even know where I would go for help.

Nobody called me for a few weeks. I called them, and someone then started scheduling things for me.

In the weeks leading up to the date of the surgery, I bought natural dye, sprinkles, and an icing mix. I got the recipe for sugar cookies that my family has used for the holidays from my mom.

Etsy has a few shops that sell anatomical cookie cutters, including the ones that I needed. I prayed to Artemis.

I had a pre-op appointment with a different gynecologist, the one doing the surgery. At that appointment, the doctor assessed the situation. She said, “I could take that out in ten seconds in the office. What if we do that instead of surgery and we send you for a saline sonogram? I’ve personally had it, so believe me when I say it’s a bit painful. I understand if you want the surgery instead, but there’s no need to do it if this is the only thing there.” Also, by the way, nobody had ordered imaging at any stage of the surgery onboarding process.

So we cancelled the surgery. Her preference was for me to have the sonogram first, and I successfully argued that I was OK with going in twice because I wanted “the largest polyp [she] had ever seen in all [her] decades of practice” out of my body immediately. The one we knew about could easily get infected at its size — for example, it bled and caused cramping when I worked out or hauled my laundry — and the many symptoms were impacting my quality of life. She conceded.

The growth was surgically removed in the office while I was fully conscious by a third gynecologist. This is when I became convinced that the first gynecologist was full of sh–t: There wasn’t blood everywhere, and I wasn’t screaming. They always biopsy growths that are removed, but they did a uterine biopsy, too, just in case my worsening flooding episodes were cancer. The only time I experienced pain and discomfort was when a giant needle of some kind of numbing agent was being injected for the uterine biopsy, and it wasn’t exactly painful, only a 3 or 4 on the scale. I just hate everything about the sensation of needles like how other people hate the sound of nails on chalkboards. The biopsy itself barely hurt, although I was warned that some people experience severe cramping. Afterward, I thought long and hard about that sense of body-alienation during the past few months and realized it was a much milder, chaste version of what I’ve heard many people experience when they are pregnant or have just given birth. And Plotinus, as reported by Porphyry, is right. Biology is really gross.

The saline sonogram next month will be painful, and it sounds like it may make me pass out if it puts too much pressure on my vagus nerve. If I do need surgery, now that I have the biopsies back and they’re negative, I can (hopefully) schedule that for when work is less hectic.

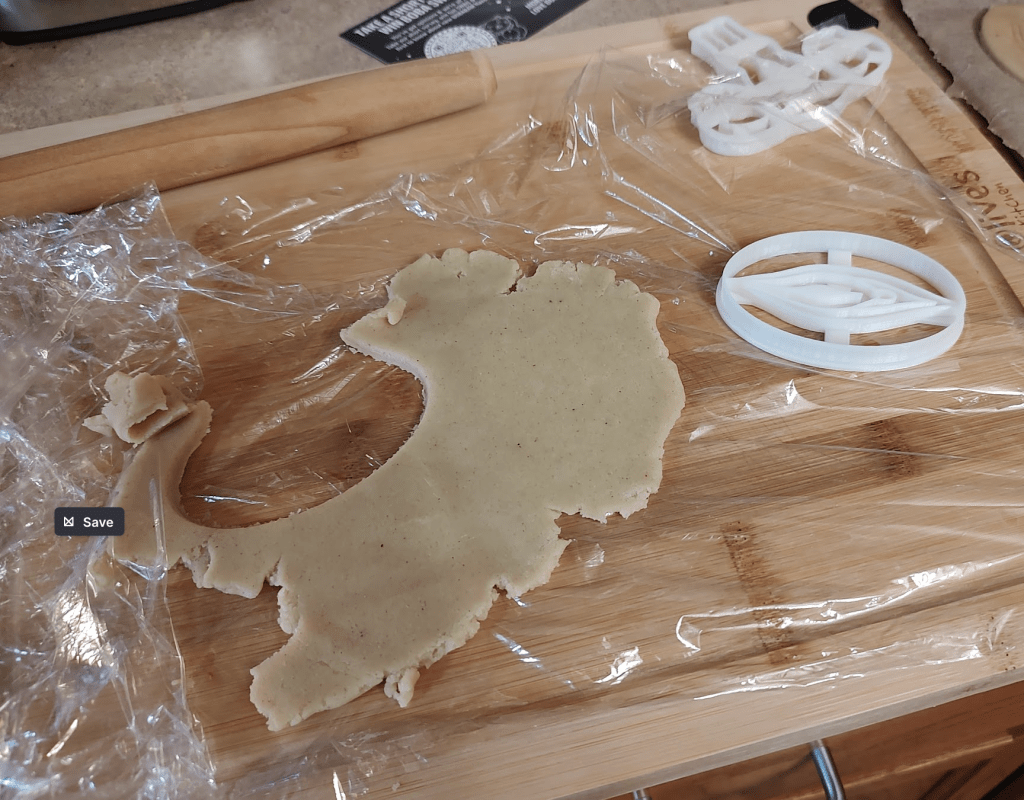

Last week, I made the sugar cookies for Artemis with the 3D-printed anatomical cutouts from Etsy. It took me two days to do it — I made the dough one day (King Arthur gluten-free flour’s texture is so nice! worked like a charm) and rolled out the cookies, baked, and decorated them the second day. I decorated them with pink icing. The surgical access point cookies had chocolate sprinkles, and the internal anatomy ones had rainbow sprinkles. When I offered them, I made a nod to Apollon and Eir, too, because I have given voice to so many rants during the past few months about medical roulette.

The reasons I decided Artemis was the primary deity at play here include:

- I make a strong association between her and gynecology due to her historical connections in marking women and girls’ life stages and her relationship to midwifery and childbearing, including her receipt of menstrual rags in some cult centers. In a Platonic context, one of her pride-of-place roles is in the life-generating (vivific) triad, where, in the third position, she “is allotted the end of the triad, moving all natural reasons into energy, and perfecting the imperfection of matter. Hence theologists, and Socrates in the Theætetus, call her Lochia, (or the power that presides over births) as being the inspective guardian of psychical progression and generation” (Proclus, Pl. Theo. 6, Ch. XXII).

- She is Apollon’s sister, and while I could pray to Apollon for this issue, the symbols involved in Artemis’ myths and historical cultus meant that this connection would be stronger.

- Artemis has slowly been incorporated into my daily practice as the guardian deity of my cats over the past few months, so I already pray to her.

While I took some photos of the cookies, I don’t think I can share them here without marking my blog due to the location of the surgical site — context is everything, and you can’t tell that something is medical merely from photos. They came out splendidly. Take my word for it. Here’s a photo of the process, with the finished products cropped out.

Instead, I’m going to send you to two image roundups from cultural heritage institutions of a more anatomically broad collection of votives and an interesting thing from Atlas Obscura. If you’re getting surgery, physical therapy, or something else, this is one way you can engage with the Gods and rest in their stillness during what is otherwise a very stressful and uncertain process.

Laskow, Sarah. “Why did Ancient Italians bury thousands of clay body parts?” Atlas Obscura, November 18, 2016. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/why-did-ancient-italians-bury-thousands-of-clay-body-parts

Moss, Richard. “Anatomical votive offerings from the Greco-Roman world,” Museum Crush. June 11, 2020. https://museumcrush.org/anatomical-votive-offerings-of-the-greco-roman-world

Patterson, Marga. “The curious lure and strange beauty of ancient anatomical votives,” Daily Art Magazine, April 3, 2023. https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/anatomical-votives/

Prayers to Artemis and all of the gods on your healing. May you recover fully and well.

LikeLike

I will extend prayers for you to the varied Healing Deities as well; I am sorry to hear that you had to endure this ordeal, not only in and of itself but also the ordeal of medical “professionals” of varying degrees of irrelevance and/or potential harm. (I’ve had no shortage of both!)

I have been in favor of this kind of practice for a long time (since the early 2000s), but have not done a lot of it myself, except fairly recently with some of the kidney stuff and kidney-shaped rocks. Anyway…

Something you mentioned here, though, gives me a bit of an idea: Proclus, even if not a household name (in most households!) is pretty influential philosophically, and has certainly influenced Christianity’s version of Platonism and Platonism-derived Christian mysticism in various ways. I’m somewhat wondering now, based on the excerpt you gave here, if the fact that monotheist and monist-leading views of the world, including in things like the (for lack of a better term) “consciousness movement,” where they basically talk about “consciousness” the same way that people used to talk about (a singular) God, presupposes mystical union, oneness, and so forth as the summit of human experience and the “Truth” of reality, etc. And in doing so, is part of the reason that they do because Proclus characterizes union as “male,” and thus this entire construction is another example of unexamined patriarchal bias and preference? Or, to use rather bolder strokes than I tend to prefer: is the union of monist/monotheist mysticism and religion/spirituality male and therefore preferred, whereas then polytheism (in focusing upon separation in the sense of individuation and making of distinctions) is female and therefore discouraged and denigrated? (The ways in which both pop psychology and some gendered interpretations of neurobiology have said that “males prefer big picture, but females prefer details” is another example of this, perhaps.) Anyway…just a possibility, not related to your overall point here, but potentially interesting and/or useful nonetheless.

LikeLike

Hail Artemis! Praise be to the Goddess that protects women! May She aid you in recovery

LikeLike