For the past few months, I have been working myself up to try something new. January 1 and a person’s birthday are the socially conventional times to commit to Big Changes, usually in an abstract way without the scaffolding to follow through. Which leads me to the first post I’ve made about minimalism in a while.

“Pre-loading” is giving me an opportunity to try things out, though, without the pressure of needing to react to an annual life goal. It’s also giving me some time to think more deeply and intentionally about what I want to do. Over the past year, I’ve had some issues with internalized ableism and processing social trauma. For most of the year, I tried to learn how to mask more effectively to not burden other people with my personality and to center other people more effectively now that I know why I couldn’t do it properly in the first place. It took a lot of energy, the exertion made me feel physically unwell, and I temporarily even started some toxic prayer habits to a Goddess to try and push through it. I started working with a therapist halfway through the year, with whom I’m learning more helpful coping strategies. It’s very important for the not-exactly-minimalism (more on that later) goal I’m working through to not be a new source of stress, especially given the broad scope.

And this goal isn’t meant to be annual. It’s … sort of an overhaul.

Rethinking Minimalism

One of the big challenges with minimalism is its connection to both the design aesthetic (which I don’t really like) and with wealthy people (who love trends and status-signaling). The ways in which minimalism evolved throughout the post-2008 crash years undermined the ways that most people were actually using it. Most people getting documentary deals and news pieces were men with some level of financial freedom. Most people on the ground working through minimalist principles were women exhausted by second-shift, invisible labor, and definitely not flush with cash.

Over the late 2010s and into the 2020s, while there had always been Christian minimalists, people started re-discovering strong Christian commitments or advertising them more, at the expense of teachings that come out of other religions (e.g., aparigraha in yoga philosophy and Hindu-adjacent spiritualities), so the space started to look really, really different — think a mash-up of rehashing various decluttering strategies and post-consumerism confessional guilt, all through their faith lens. There’s been a contraction of interactions with people outside of that worldview as well, at least judging from who seems to be networking with whom and which commenters spark conversation.

There was a parallel trend of people who, based on the average age (although some may be in their late 30s like me), must have been active in the mid- to late 2010s’ international youth climate movement, and this group started to explicitly fuse minimalism with environmentalist and de-growth ideas. Their content hews closer to statistics, data, and evidence-based solutions, and they sometimes didn’t even call it minimalism.

From a Platonizing and polytheistic perspective, a lot of what we are grappling with as we navigate a world of excess consumption in which the most vulnerable people are starving goes back to Plato. He did explore some ideas in the surface-value story of the Laws related to capping maximum income. However, Socrates got a bit spicy about overconsumption and greed in the Apology at 29e (trans. Chris Emlyn-Jones and William Preddy in 2017, the Loeb version):

Most excellent of men, as an Athenian, a citizen of the greatest of cities and one most distinguished for wisdom and strength, aren’t you ashamed to be spending your time acquiring as much money as you can, ever gaining reputation and honor, but show no interest or concern for wisdom and truth and seeing to it that your soul will be in the best possible state?

Nothing In Excess

During lockdown, I found a research article from Millward-Hopkins et al. called “Providing decent living with minimum energy: A global scenario.” It showed that it was possible to limit total energy consumption to 1960s levels while supporting a larger population than we had during that decade, all without forcing people to become monks, just by streamlining transportation, reducing consumption, making housing more efficient, and eating fewer resource-intensive foods. Last year, “How much growth is required to achieve good lives for all?: Insights from needs-based analysis” was published by Hickel et al. It showed something very similar, although it placed a greater emphasis on shifting output to the types of production that actually help people from things that are excessively energy-gluttonous.

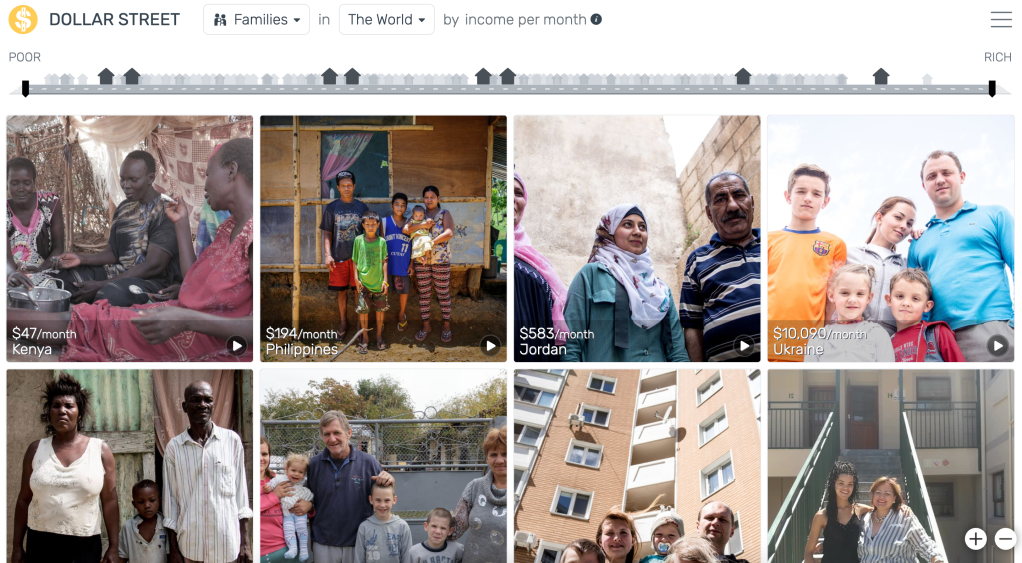

Essentially, what is required by these pieces is for people who are overconsumers to consume less (and pay more into social programs) so that there is more energy available for those without the same level of choice-driven consumption to increase quality of life — basic things like sanitation access, a washing machine, electricity generation, and healthcare equity. If you’ve ever browsed through the development level photography collections on Gapminder (called “Dollar Street”), or if you have lived or worked in areas where people aren’t able to meet their basic needs, you have an idea of what I’m talking about.

Since my autism diagnosis and starting to reflect on things happening around me in a slightly different way, I’ve also grown increasingly peeved by people thinking that the capitalism-communism gradient is real. It’s no more real than a Buzzfeed “Which Lord of the Rings Character Are You?” or “What Kind of Dancer Are You Based on Your Sun Sign?” quiz. In the partisan realm, I’ve often been left speechless at watching certain partisan groups saw off the legs of our own social safety net out of fear of socialism or communism, causing deep suffering to lower-income families. It seems that many are growing increasingly disillusioned by this now that we’re all so aware of what life looks like in countries where residents and citizens have real social amenities and are getting something out of the taxes they pay (other than warmongering).

Thinking of acquisitiveness on a hoarding vs. sharing continuum is a better way to consider it, if we had to reduce something complex down to continuums at all. We’ve based our current society on the idea that more is always better and that hoarding is good as long as you have a house big enough to fit all of what you acquire and a salary resilient enough to absorb the costs. It reminds me a lot of this passage from Damascius (Life of Isidore, §18, trans. Polymnia Athanassiadi):

He used to say that, just as the soul has three parts or types (or whatever one chooses to call them), so too there are three different ways of life, each of which contains all three elements while receiving its overall shape from the dominant one, which also gives it its name. Reason is the main influence on the first of these, which could be called the Cronian life, the golden race or the generation akin to the gods, celebrated in the guise of myth by poets seated on the tripod of the Muse. Emotion influences the second, which engages in wars and battles and generally fights for the first prizes and for glory and which we continually hear talked about by history. Appetite rules the third, which is totally dissipated, corrupted by unbridled wantonness, dominated by base and womanish thoughts [viz. he really means acquisitiveness, emotionality, mental and moral weakness, lack of self-agency, and associated traits; as sexism was prevalent at the time, adjectives like “womanish” were used to gloss what they really meant], associated with cowardice, wallowing in swinishness of every kind, avaricious and petty, merely wanting servitude, achieving nothing noble or free, servile and weak, measuring happiness solely in accordance with the belly and the pudenda, totally without nobility of spirit; like a body dumped in a corner, lying enervated and incapable of movement. And he showed the life of the men who are now in the service of generation* to be much baser even than this.

There are also many things brought up in Simplicius’ commentary on Epictetus, where he is providing a Platonizing lens of Stoicism, such as his comments at 115,10 until 117,10. Here are a few quotations pulled from those sections:

- “This is just the way that we should go through life in relation to our own instrument [the body]: We should supply only what it needs, and in our choice of foods and drinks, we should select the most easily provided and most natural of the things that keep the human body nourished according to its nature.”

- “Socrates was said to use the same clothing both summer and winter; and though it is indulgent by comparison to Socrates, it will be sufficient if we vary our clothing for the extremes of the seasons, using both linen from the earth and the fleeces of familiar animals.” (He then goes on to contrast this with status-driven excesses, which at the time were for silk and imported exotic animal pelts.)

- “In our case, let us have a house, but one that satisfies need both in its size and ornamentation […] but not some establishment with thirty beds, covered with brightly colored mosaics throughout on the walls and floors, or different lodgings for each month of the year. Our needs do not demand such things, and it is an unfortunate fact that anyone who has grown accustomed to them is dissatisfied with everything else. And it goes without saying that people who have become attached to such things inevitably locate their happiness in them and completely forget themselves […].”

And again at 126,42-127,4:

Likewise in the case of possession and the things that serve the needs of the body. If someone oversteps the measure of need and the limit it imposes, ‘from then on he gets carried away’ into limitlessness, piling up things on things, until he has been carried away into the deepest depths of indulgence and empty vanity (the sources of his wrong turn), and of the needy indigence (which follows the wrong turn), and of pinching oppression (which follows that).

If we acquire ten possessions, we want twenty; and if we get twenty, we want forty, and so on; and there is no end of this propulsion into the chasm of insatiability. It is clear that for anything accepted for the needs of the body, possession that steps beyond the limits falls into limitlessness. And in the end we actually forget the goal and forget the need to which it contributes: the need of the body. That is why we often even betray our bodies owing to the insatiability of our acquisition of possessions.

Changing Things Up

All of that has left me with an interesting question.

What does it actually look like if we stop the hedonic treadmill and commit to a reasonable lifestyle? Like … really?

How would my choices of how to do this differ from someone else’s? 1+3+6+12+3+2 = 27. And so does 7+3+2+4+8+3. There are many ways to approach energy use with temperance.

For example, here are the things that I am weighing:

- A plant-forward diet is the most sustainable diet. It’s not the same as a vegan or vegetarian diet, as it accounts for land use areas suitable for herding, and it acknowledges that people are individuals and have different genetic and environmental factors that determine what is best for them. However, with the fibroid gone and no longer squeezing my intestines into my spine or giving me horror movie levels of bleeding, I’m able to eat chickpeas, tofu, and some other legumes without pain, and I don’t need to monitor my iron intake as carefully. What is the most sustainability-aware way to eat meat sources if I want to prioritize collagen (for joint health), vitamin A (my body has the gene that makes it extremely bad at converting plant sources), iron, and B12? I mean, protein is protein, so that’s not really a big factor here. So: Canned sardines, mussels, eggs, ghee, marrow bones, chicken bone broth, and chicken meat from making broth. A bit of red meat here and there. I really love the texture of silken tofu and soft chickpeas, so this isn’t a big deal to me.

- Gluten exposure makes me vomit. Ergo, I don’t use bulk bins, as people are inattentive when they’re using the scooping spoons, and sometimes stores re-do which bulk areas have gluten-containing products without properly cleaning containers. I’ve also found that incorporating some prepared items is easier on my weeknight mental fatigue and leads to less food waste, which also means packaging. So I do have plastic waste from that packaging.

- Technically, the apartment I have has two bedrooms, although the smaller one would not be able to fit a normal bed and dresser. Living alone has always been a splurge thing for me to avoid gluten cross-contamination, and based on my student experiences, living with non-polytheists is uncomfortable because they don’t understand the religious thing. Plus, I guess living alone makes it easy to not have to mask being weird all of the time. However, even already sharing my space with three cats, it would be more ethical and sustainable to get a roommate. And it would be less expensive as cost of living goes up. And living with other people does provide a buffer against the impacts of the loneliness epidemic. A conundrum, but maybe things are OK given how hard it would be to Goldilocks this.

There are also some things that I do not have to weigh as much. I already primarily buy used clothes (although, like many, I have more than satisfice), and I only fly once every few years when the work conference I go to is not accessible via train. I don’t have a driver’s license — yes, for brain reasons, but I guess the sustainability thing is a silver lining because I’ve never been able to take car mobility for granted, and I don’t have an entrenched driving habit. I bike, walk, or take transit everywhere unless I’m carpooling with a friend.

Over the past few months, I’ve been balancing my consciousness about food waste (this week was bad, admittedly, because my oven broke two weeks ago, and the part to fix it is still on order according to my landlady’s handyman) with eating more plant-based sources to see how it goes, and it’s going pretty well. I’ve also strengthened my impulse to check for used items before buying things new. For new items, I bought a safety razor during a sale over the summer once my ancient plastic razor with replaceable heads (which I bought in bulk one time 10 years ago … it’s taken me this long to go through them) was no longer usable and a replacement (eco-friendly) electric toothbrush. Hermes has blessed me this year in that everything I’ve needed to replace has broken when there’s a pretty deep sale on a replacement.

Eventually, I might even get over the anxiety about how to go about re-homing a few shrine things (and a few agalmata) that are currently being stored, but I’m not sure of the religious protocols for that, as nobody talks about this sort of thing or has published divination-backed protocols and processes on how to declutter sacred items with sensitivity. It’s not pious to treat sacred items as mere things, and it’s not sustainable to hoard what could be used by others. I’d legit buy a book called Shrine Maintenance: Building, Keeping, and Decluttering Made Simple, if it were written by a polytheist specialist. And I bet a lot of people need that book more than I do based on some of the spiritual materialism I’ve seen on social media.

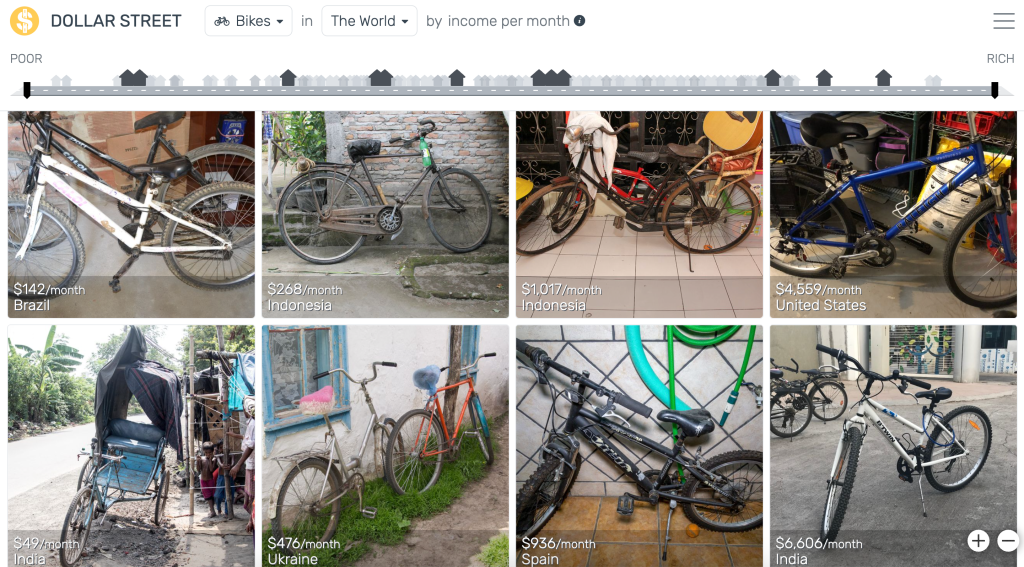

The cost of living has also gone up so much that it’s also prudently frugal to aim for a sustainable lifestyle change without the trap of an austerity mindset or a full-on moratorium on, say, gift spending. I’ve started donating to Wren.co and Only.one, which support decarbonization and nature resilience projects — even though it’s my position that corporations should be paying for the pollution they create. There are also growing signs that people are getting fed up with financial hoarders who get rich off of exploiting others or Influencers who make lots of money off of livestreaming their greedy excesses in haul videos and cultivating appetitive longing in their viewers. Like, the nicer instinct in me wonders if the wealthy are hoarding money in part because they’re having the rich person version of decision fatigue/paralysis … as when normal people are weighing, say, which commuter bike to buy and run into the ground for the next 20+ years … and then they don’t end up doing anything prosocial with it, so one could argue that taxing them more does help them help themselves.

By 2026, I will have a better idea of what to do and how to do it, although I want enough flexibility to respond to the latest research. The backlash against expertise in the USA has made me very sensitive to ensuring that I am not making that problem worse through my own actions. As one example, this report came out very recently about how to build a climate-sufficient lifestyle, and I haven’t read it yet.

All in all, I think this new direction isn’t exactly minimalism, and it isn’t exactly not. The report above calls it “sufficiency living.” It reminds me of a consumption version of the rational dress movement, when women rose up to stop wearing clothing that restricted movement and caused health issues. I think the nothing in excess (μηδὲν ἄγαν) emphasis is far more in keeping with what makes sense, and I’m excited to see how it goes. The God gave us that maxim for a reason.